Well, if there were a contest for best day of the trip- this would sure be at the top. We paddled ashore and tied up the kayaks at the base of some coco trees. Here, a river met the ocean and a couple of kids were playing in the brackish water there. From here, we walked up to a cluster of houses and then on up a path headed towards the valley. Land crabs were everywhere! They dig holes all over, and are lurking around until they see you, after which they dart to the nearest hole.

The people we met were very kind and generous- putting up with our very bad and broken French language skills. Many of them were tending gardens and farm plots- we saw pamplemousse, pineapple, coconut, banana, peppers, mango, papaya and more. We bought some fruit for the hike from a couple living up this path; very generous exchange even though we couldn’t really communicate with words.

The people we met were very kind and generous- putting up with our very bad and broken French language skills. Many of them were tending gardens and farm plots- we saw pamplemousse, pineapple, coconut, banana, peppers, mango, papaya and more. We bought some fruit for the hike from a couple living up this path; very generous exchange even though we couldn’t really communicate with words.

Headed up the valley further, we continued on a 3.5 hour hike that wove its way through the forest along an ancient roadway. We could see in the shadows and under the lush vegetation the remains of many, many homes. Some of the books say that as many as 2000 people lived in this section alone.

Finally we reached an improbably steep canyon, lush with vegetation and it had tropic birds circling high in the sky. We continue on, watching for rock fall, and end up at the dead end of the canyon- a 1300 foot tall waterfall. We, of course, go swimming in it! To get all the way back, we swam under a huge boulder that had fallen—then on the other side the raging torrent of cold water was coming directly down on us. Over millennia it had carved a huge cavern in the basalt rock, leaving a cathedral of stone flanking the falls on both sides. Wonderful.

On the hike back, we stopped by another home and met Tiekee, who gave me a lesson on how to husk coconuts. He said he had husked 500 that day! I think I need more practice. He wanted to trade me hats and sunglasses- but I managed to trade for the Vandal flag I had brought instead!

Later we met him again with fish he had speared. Among the biggest was the parrot fish. He took a small boat out and with fins and a spear dove to catch these fish. Pretty impressive!

Finally, I had a chance to talk to some students from Lapwai, back home in Idaho. Good to hear some voices from home! Thanks everyone for the great questions!

Islands: Global Climate Change

What major impact might climate change have on islands?

Climate change is a topic often headlining news stories in print, radio, television, and on-line news media sources. Scientists and research institutes publish scholarly articles and papers on many different aspects of the topic. Commentators publish opinions on all sides of the topic. The general public often scratches its head and wonders which voices they should listen to, and what to believe about climate change.

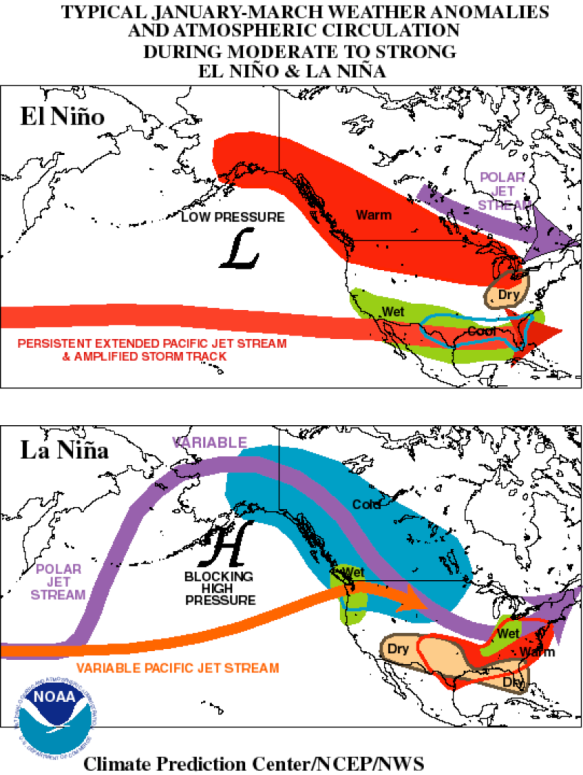

Scientists who study the planet’s climate system focus on many of the different components of the system, and try to understand how the parts of the system function, how they work together (or in opposition), and what the impacts of a shifting climate are predicted to be. They can also study the events that happen right in front of their eyes. Glaciers advance and retreat, wind patterns weaken and reverse, drought afflicts one side of a mountain range while flooding occurs on the other side, and some planted crops provide record harvests while others wither and wilt.

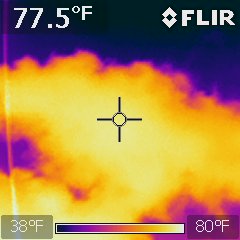

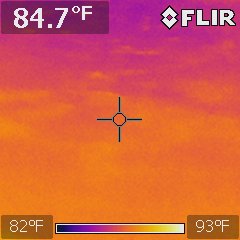

Oceanic islands provide interesting natural laboratories for science. The landscapes and the ecology of islands can be quite sensitive to a shifting climate. If the local and regional temperatures get too high or too low, it can influence growth cycles for plants and plankton, which can cascade through the food web as populations skyrocket or crash. If the local and regional rainfall decreases, fewer nutrients may wash into the ocean off the islands, resulting in slower growth rates within the ecosystem, but also slower rates of island erosion. Conversely, increasing rainfall may enhance growth rates in the ecosystem with an influx of nutrients at the cost of increasing the erosion rate, loss of topsoil, and possible damage to terrestrial ecosystems on islands.

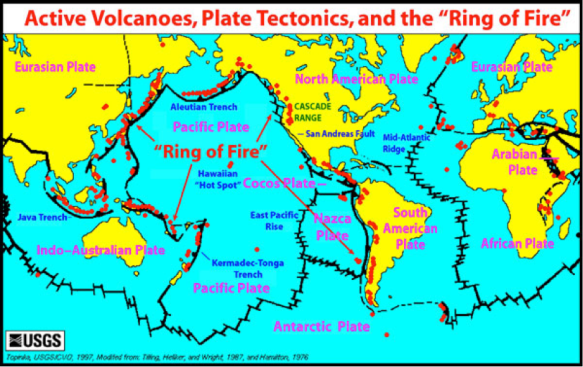

Another potential impact on oceanic islands related to climate change is how the oceans react to a warming or cooling climate. On a global scale, a cooling climatic trend would result in more precipitation falling on the continents (especially at high latitudes and high elevations) in the form of snow rather than rain. In a cooling climate, snow will accumulate year after year, slowly changing into ice and building large storehouses of frozen water that we call glaciers. In a cooling climate that develops into an Ice Age, global sea level can actually drop as more and more water is literally frozen in place on the continents and the polar ice caps, and therefore not in the global oceans. During the last major Ice Age, about 20,000 years ago, global sea levels were as much as 120 meters (~360 feet) lower than mean sea level today. An image depicting this sea level for part of northern Europe is shown just below.

So what happens if the global climate isn’t cooling, but is warming? Again, thinking about global climatic patterns, a warming climate might generally mean less precipitation falling as snow and more falling in liquid form as rain. More rainfall instead of snowfall, and warmer temperatures, could mean that glaciers would be retreating instead of advancing. The global storehouses of frozen water would gradually melt as warmer air temperatures and relatively warmer rain help to melt the glaciers in the mountains and ice sheets and caps near the poles. Instead of being stored in frozen form, more of the global water supply would runoff into the ocean basins. More water in the oceans would give way to sea level rise. Additionally, warmer conditions on the planet would cause the global oceans to warm up… and water expands as it warms up… leading to even more sea level rise. Near the extreme end of current climate change projections, sea levels could potentially rise as much as about 60 meters (~180 feet). The image below shows the impact on the shoreline for the same region of northern Europe.

If this is a possible future for Europe, with its vast coastline and dependence on maritime travel and commerce, imagine… what might happen to oceanic islands? Any amount of sea level rise would impact oceanic islands. The tides and waves would reach higher onshore, eroding the nearshore zone to a much greater extent. Low-lying areas would be inundated by salt water, including most of the towns and cities, which have historically been built on the flat, sandy areas near the bases of the volcanic mountains that form most oceanic islands. Using the on-line Google Maps tools at http://flood.firetree.net/ by Alex Tingle, we can see what an extreme sea level rise would do to Nuku Hiva’s shorelines. It wouldn’t completely submerge the island, but it would pinch off two peninsulas, creating two new islands, and it would completely submerge the towns on the island.

Is this science fiction? The Alliance of Small Island States has 39 member nations around the world. They are actively engaged in the scientific and political debates regarding climate change, sea level rise, and other threats to their maritime cultures and economies. Even if extreme sea level rise does not occur, any significant sea level rise will have physical, cultural, and economic impacts on island nations. Consider the Republic of the Marshall Islands, located in the Pacific Ocean at about 9 degrees North latitude and 168 degrees West longitude; the Republic is composed of 5 islands and 29 atolls whose average height above sea level is 6 ½ feet. Sea level rise of even a single foot would be significant to this entire country.

In May of 2011, the Columbia Law School’s Center for Climate Change Law hosted a conference that addressed legal issues related to sea level change: “Threatened Island Nations: Legal Implications of Rising Seas and a Changing Climate”. The people of island nations take sea level change seriously enough to start thinking about how to collect compensation from other nations who may be contributing climate change; this has been a consideration since at least the 1980’s. An interesting side note to the legalities of climate change is that such legal action was a critical element of author Michael Crichton’s book State Of Fear, which is an action-adventure novel with a climate change plot.